To football lovers of a certain age, naming that tune in one second isn’t just easy, it comes with the added ability to transport people back in time, a quarter of a century in a heartbeat. Even before Luciano Pavarotti fills his lungs, as the lilting melody of the chorus of Nessun Dorma starts to rise, via musical time travel we arrive smack bang in the midst of Italia 90.

Some critics of the day found it hard to care for that World Cup. For the purists, it lacked the required flamboyance, defending was cynical, and the final reeked of ill-tempered drudgery. But to assess Italia 90 only according to those parameters is to miss all the virtues that gave it meaning. It might be pushing it slightly to say that everything I learned about life I learned at that World Cup, but if all Italia 90 kids don’t admit that month was transformative, I will consider eating my Ciao hat. (That was the very stylish mascot, by the way – a stick man with tricolore colouring and a football head.)

It might not have been a World Cup of great games, but it was a World Cup of memorable tales and epic emotions: Roger Milla shook his 38-year-old hips at the corner flag for himself, for Africa, for old people anywhere who don’t give up believing in the unbelievable. Totò Schillaci smashed in shots, wheeled off with his crazed eyes virtually popping out of their sockets, and became an unlikely hero. Frank Rijkaard and Rudi Völler were entwined in a spitting red card fandango. David O’Leary kept his legs from buckling to score a legendary knock-out penalty. Gazza, as everybody knows, cried but the scene gains depth with that concerned glance that Gary Lineker threw at Bobby Robson. Italy wept as they were niggled through the semi-final and left vanquished by Argentina in Diego Maradona’s adopted city of Naples.

And then in the final, to paraphrase Lineker’s famous phrase, 22 men chased a ball around (which became 20 after two red cards) and at the end, the Germans won. Franz Beckenbauer entered that special double club of World Cup winners as player and manager.

But there is a broader picture even beyond the stories embroidered on the pitch. Italia 90 was the bridge from old style World Cups to the new. Four years afterwards, Fifa began its quest to spread its tentacles, to take the show into territories where football was less rooted. Since departing Rome’s Olympic Stadium in 1990 with Lothar Matthäus’s arms around the golden trophy, three out of the subsequent six World Cups have taken place outside the traditional powerbases: USA 94, Japan and South Korea 2002, South Africa 2010 (alternating with three historic football countries in France, Germany and Brazil). If we factor in the next two competitions currently set for Russia 2018 and Qatar 2022, that trend towards developing markets carries even more weight.

Italia 90 took place in an era where attending a World Cup was not an outrageously extravagant idea for an adventurous football fan. There was no notion of hotels or restaurants bumping up their prices by insane percentages to rip off visitors. Tickets floated about at face value if you looked hard enough in most host cities, certainly in the group stage. Word got round in the streets of the names of shops and bars which were selling match tickets up to the eve of the game. There were no fan parks, it was all improvised for better or for worse. The idea of a group of corporate punters forming a crocodile in branded baseball hats following a pretty girl holding up a sign bearing the name of a vast conglomerate as they march to a tented village would not have got very far. That audience didn’t want to go to football anyway then.

Confession: I retain the same blind love for Italia 90 today that struck me then. I was 18 years old, and it was beyond exciting for anyone who experienced it as a seminal World Cup experience. Luckily for me, not only was I at the right time of life to be able to plan my month around watching games, filling in wallcharts and so on, I was also old enough, and had enough free time in a post-exam lull, to actually go. The decision was spontaneous, made in the crazy excitement of the opening game, which I watched on telly with a couple of friends, Nick (Leeds United) and Paul (Everton).

Cameroon v Argentina was dubbed the Miracle of Milan. It was symbolic of how entrants from Africa were regarded that the BBC commentator described them, in a manner that seems so patronising today but was not intentional then, as “happy go lucky fellows”. They were able enough to not just compete with Argentina, the reigning champions, but to defeat them.

We looked at each other after the final whistle confirmed one of the most improbable of all World Cup results with the same thought at the same time: Let’s go.

After a quick consultation with the wall chart, to determine who was playing where and what would be the best place to aim for, it was destination Genoa and Turin, armed with a couple of hundred quid and a sleeping bag. A fantastic group – Brazil, Sweden, Scotland and Costa Rica – was a great attraction, as was the fact it was significantly distant from England’s base in Sardinia. We wanted to enjoy the World Cup as peaceful football fans, without the bother of reputations shadowing our every step.

There, with that awkward sentence for an English football-loving person to write, is another key to why Italia 90 mattered so much. In fact maybe it’s part of the explanation for why it matters so much more in England than in many of the other participant countries.

God knows English football needed a tournament to salve wounds, to mend a broken reputation overseas, with the tragedies of Heysel and Hillsborough – which didn’t have the luxury then of the truth that is emerging at the current inquests all these years later – still so close in our minds and hearts.

Pete Davies, the author of the outstanding account All Played Out, summed up the ambience of the time in a recent interview with Esquire magazine. “The way the game is now derives, to a very great extent, from the transformation that Italia 90 affected. Prior to Italia 90 football in England was perceived as a squalid, hooligan-ridden, embarrassing sump of gormless violence. Our team was crap, our supporters were worse, and you did not talk about it over dinner.”

We headed by train and ferry to Genoa, far from what was expected to be the madding crowd. We stopped off in Turin, the venue for Brazil’s opening game against Sweden. Then on to Genoa, to take in the surprise of Costa Rica beating Scotland, before Andy Roxburgh’s team redeemed themselves a bit by seeing off Sweden.

There was not enough accommodation for the many meanderers who had made Genoa base camp. The city officials decided the sensible thing was to keep the football fans together, so we were invited to sleep in the railway station. The daily routine went something like this: At around 6am, before the commuters had the misfortune of stepping over a series of comatose bodies on their way to work, the police gently woke us from our slumbers, we packed away our sleeping bags, dumped them in left luggage, and availed ourselves of the station showers for a wash and brush up. Some couldn’t quite manage that so ended up taking a soap and a shave in the ornate fountain which is the centre piece of the beautiful Piazza de Ferrari.

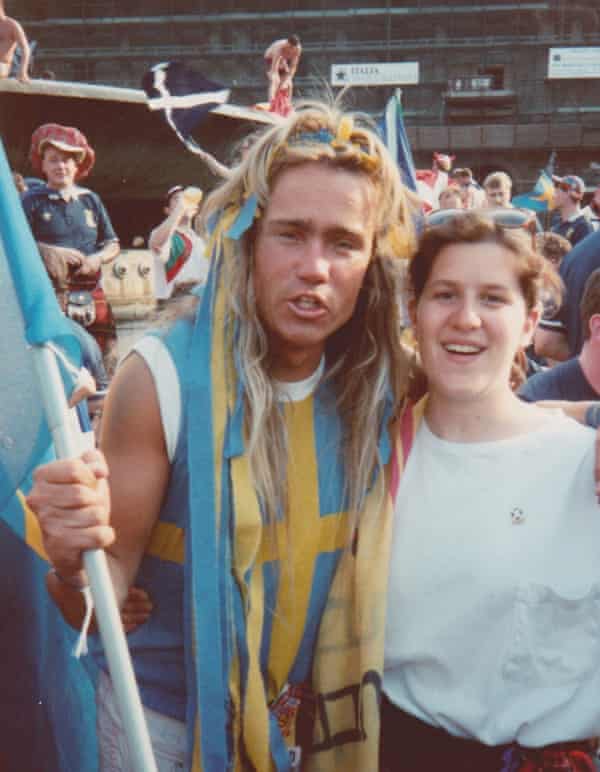

The days were filled with impromptu football games in the square (there was a local kid who spent the whole time being Roberto Donadoni), the search for tickets, watching matches in cafes, conjuring up ways around the alcohol ban, enjoying the hospitality of the Genovese who brought out their children to have pictures alongside the colourful visitors and invited fans in for giant bowls of pasta.

It was a true example of a catchphrase later bastardised by Fifa – this was the “football family” where anyone from anywhere was invited for one gigantic party. The evenings became louder, naturally, as the three main groups in town – the Scots, Swedes and Italians – joined in each others’ songs.

On the day of Scotland v Sweden word got around that a band of pipers, in full regalia despite the sweltering heat, would lead a march through town to the Stadio Luigi Ferraris. Thousands of folk in kilts and Viking helmets mingled as they followed the music and danced to the match.

Back in England, the team’s progress, and the lack of the kind of trouble everybody feared, was a huge part of the radical change that was coursing through our football in a post-Heysel and Hillsborough world. People who sneered at the game, accustomed to seeing only ugliness, found themselves unexpectedly swept along. Gascoigne, the “daft as a brush” boy who played with such spontaneity and wore his emotions so readily, captured public imagination, and presented a very different image of English football.

In the coming seasons, with stadiums being reformed to meet all-seater requirements, Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch expressing the fan’s condition, the restrictions on foreign players being relaxed to open the doors to talent from across the world, the rebranding of the Premier League and arrival of Sky glitz, football would become more glamorous, more welcoming.

The third-place play-off, contested by two desperately disappointed teams in England and Italy, turned out to be uplifting. After the medals had been doled out, all the players of both squads stood side by side clutching floral bouquets and they took a shared bow. It was an important moment, a bridge-building act of friendship and respect just five years after the nightmare of Heysel.

For all that it means to English football, to Italians as the hosts whose fairytale didn’t come with a happy ending, to Cameroonians who hoped it would be the gateway to a major breakthrough for African footballers, there are also some other greatly changed nations for whom Italia 90 still has resonance. Four countries no longer exist in the way they did then. It was the last World Cup in which West Germany competed (unification came later in 1990). Yugoslavia began to break up in 1991. Czechoslovakia split in 1992. This tournament represented the last appearance at a major finals of the Soviet Union team, as by the time the European Championship came around their place was taken up by the CIS, which was effectively just Russia.

Maybe it wasn’t the best World Cup you will ever see. Not many Brazilians or Dutch will reflect with much fondness, which given their status as aesthetic football nations is revealing. The statistics are not positive – the fewest goals per game in the competition’s history and the most red cards at that point.

But still, it was so profoundly important. If anyone wants to squabble about that they could do worse than gawp at Roberto Baggio’s salsa through the Czechoslovakia defence or Dragan Stojkovic’s masterpiece against Spain, listen to New Order’s World in Motion, marvel at the reaction to François Omam Biyik’s opening day goal and the madness of Benjamin Massing’s tackle to mow down a galloping Claudio Caniggia to make the Miracle of Milan, read All Played Out, and cap it all off with Nessun Dorma.

As the man himself sang with such immense, Italian gusto, “Vincerò! Vinceeeeeeerò!”

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/football/blog/2015/jun/15/italia-90-world-cup-specia

0 Comments

Post a Comment